Lynne Rudd sat in a pink lawn chair outside an Edina library on Monday, ready to experience an eclipse for the ages.

"There it is! Look at that … Wow!" she said, as the moon blocked nearly 80 percent of the sun. It was a fleeting moment before clouds obstructed her view and the crowd around her groaned. "Where did it go?"

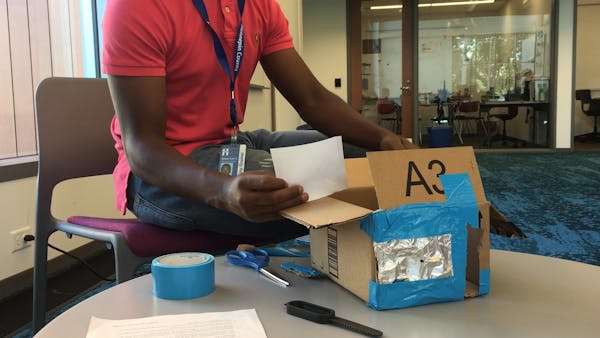

Across most of Minnesota, overcast skies granted only glimpses of the much-anticipated solar eclipse. In the Twin Cities, throngs of people gathered on corners and scattered across parks to stare upward, hoping to catch a quick glance. Crowds with special glasses and foil-lined boxes on their heads erupted in cheers, oohing and ahhing as the eclipse peeked through for short stints, a sliver of the sun's bright orange peering out from behind the passing moon.

Outside the Science Museum of Minnesota in St. Paul, when 9-year-old Madi Rosario's mother told her the sun would go dark, the girl responded: "What, is it a magical day or something?"

In a way it was.

Monday's eclipse inspired enormous excitement because it was one of the few times a total eclipse has been visible across a broad swath of the United States, said Jack Ungerleider, a Science Museum volunteer. The last time was in 1918.

Eclipses occur when the moon lines up between the Earth and sun along an imaginary line that represents the intersection of the orbital planes of all three bodies. Most people saw only a partial eclipse.

The next partial solar eclipse in the U.S. will occur in 2023, and the moon will cover slightly less than half of the sun as seen from Minnesota. There will be a total eclipse in parts of the country six months later, but it will cover only three-quarters of the sun here.

The wait for the next total solar eclipse visible in Minnesota is significant — 2099. The last time the state got to watch one was in 1954.

Minnesotans used the eclipse as a chance to share a rare-in-a-lifetime experience.

Outside the Hennepin County Southdale Library in Edina, families gathered on chairs and blankets. Some brought popcorn. Strangers introduced themselves to one another while waiting in a long line to look through a telescope.

Librarians instructed the crowds that they could give out only one pair of eclipse glasses per family. Diane Kaplan of Edina was alone in line when Barbara Theirl of Burnsville turned and said, "You can be our family." They shared the sunglasses as Theirl's 6-year-old grandson, Simon, cut holes out of foil to wrap in front of a shoe box.

For some cultural and religious groups, the eclipse had special meaning.

Several Minnesota mosques called followers to special prayers. The Council on American-Islamic Relations explained that a similar solar eclipse occurred on the day that the prophet Mohammed's young son died.

In Grand Island, Neb., a group of Minnesotans performed a Dakota ritual as the sun became a crescent. Rick Green of St. Cloud lit a ceremonial pipe and passed it around a circle, each person reciting a phrase that meant "We are all relatives."

Exploring science

Other groups emphasized the science behind the phenomenon.

At the Science Museum, where nearly 6,000 people swarmed three outdoor patios and the back lawn, NASA Solar Ambassador David Goldstein came with props to explain the astronomical choreography. Holding a globe beach ball in one hand and a moon on a stick with the other, he explained to a circle of kids how the moon cast a moving shadow across the Earth.

But the real drama of the afternoon was the game of peek-a-boo by the clouds.

Seven-year-old William Ndegwa pronounced his glimpse of the eclipse "incredible." His mother, Maureen Ndegwa, said she brought him because it's important for children to experience the wonders of the world, and she hoped it would inspire an interest in science for him.

Other eclipse seekers watched how earthly creatures responded.

Certain animals are sensitive to the length of the day, said Carrol Henderson, nongame wildlife program supervisor with the Department of Natural Resources. It could be seen at the Minnesota Zoo, where 16 red kangaroos and 25 wallabies were up and grazing as if it were dusk instead of lounging in the shade to conserve energy. A male albino joey was play-boxing with his mother.

"This is just what we expected," said zookeeper Angela Carlson.

Going the distance

Scores of Minnesotans who traveled to the path of totality — a 70-mile-wide band stretching from Oregon to South Carolina, where the moon's rare march across the sun would be most complete — had better luck with weather.

Dave Williams and his friends, about 20 members of the Astronomy Club of Central Minnesota, made the trek from St. Cloud to Grand Island to watch. The parking lot of the Stuhr Museum, a pioneer living history village, was studded with Minnesota license plates. Others flew in, including 157 on a chartered jet that departed Monday morning and would return to the Twin Cities in time for dinner.

Amid kettle corn stands, taco trucks and a NASA livestream, the crescent of the sun shrank in on itself, and the prairie grasses took on an eerie, black-and-white cast.

"That's totality," shouted Williams, a former earth science teacher and planetarium director at St. Cloud State University who led the group.

The protective glasses came off. There were gasps and laughter and cheers. People embraced.

"I want to come to the next one and the next one and the next one," said Williams, whose T-shirt had a picture of Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. Underneath, it said, "Hollywood Ending."

Staff writers Josephine Marcotty, Erin Adler, Faiza Mahamud, David Chanen and Matt McKinney contributed to this report.

Pam Louwagie • 612-673-7102

13-year sentence for unlicensed driver who fatally hit motorist while fleeing police in Oakdale

Man killed in Minnetonka by law enforcement started gun battle with deputies, BCA says

FAFSA completions in Minnesota drop amid flawed efforts to update form

Wisconsin Republicans ignore governor's call to spend $125M to combat 'forever chemicals'