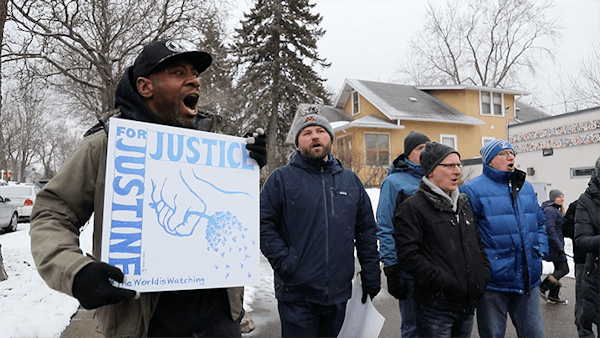

The Minneapolis police officer who fatally shot an unarmed woman last July was charged Tuesday with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter eight months after the case sparked protests, international outrage and the firing of the city's police chief.

Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman said Mohamed Noor, 32, acted "recklessly" when he fired the shot into the dark that killed 40-year-old Justine Ruszczyk Damond after she called 911 to report a suspected rape in her south Minneapolis neighborhood.

The shot came after Noor and his partner, Matthew Harrity, had driven through the alley behind Damond's home, saw no suspicious activity and were preparing to leave when they were surprised by someone outside the police car. Harrity, the driver, told investigators he was "spooked," feared for his life, and took his gun from its holster before Noor reached across and fired his weapon out the driver's side window.

Harrity looked out his window and saw Damond clutching her abdomen with both hands. He recalled her saying, "I'm dying," or "I'm dead."

Freeman said the investigation of the shooting uncovered no evidence that Noor "encountered, appreciated, investigated or confirmed a threat that justified the decision to use deadly force."

"Instead, officer Noor recklessly and intentionally fired his handgun from the passenger seat, a location at which he would have been less able than officer Harrity to see and hear events on the other side of the squad car," Freeman said.

The shooting showed evidence of "a depraved mind," as the charges are defined, and "culpable negligence," Freeman said, though he acknowledged that proving that to a jury is "a daunting task."

Damond's death was the third controversial police shooting in the Twin Cities in recent years — events that led to calls for greater police oversight, improved community relations and better training for officers.

The case sent a shock wave from Minneapolis all the way to Damond's native Australia, horrifying many people there as a grim example of aggressive U.S. police behavior.

On Tuesday, her family, including fiancé, Don Damond and father, John Ruszczyk, applauded the charges in a joint statement, calling them "one step toward justice for this iniquitous act."

"No charges can bring our Justine back. However, justice demands accountability for those responsible for recklessly killing the fellow citizens they are sworn to protect, and today's actions reflect that," the statement read.

Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, who was appointed after former Chief Janeé Harteau was ousted following Damond's death, announced Noor's immediate departure from the department. He also emphatically apologized to the Damond family.

"I am committed to ensuring that myself, and every member of the MPD, learn from this tragedy," he said in a statement. "It is imperative that we as a Police Department build trust in those places where it did not exist, and increase the trust in those places where it has been shaken."

But Noor's attorney, Thomas Plunkett, said Noor acted appropriately. "The facts will show that Officer Noor acted as he has been trained and consistent with established departmental policy," he said in a statement. "Officer Noor should not have been charged with any crime."

Noor surrendered to Hennepin County deputies after a warrant was issued for his arrest Tuesday. He was later booked into the county jail on $500,000 bail for charges of third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. He is expected to make his first court appearance Wednesday and faces up to 35 years in prison if convicted.

Freeman told reporters that the case "would've been done much quicker" if some of Noor's fellow officers had agreed to cooperate with his investigators, repeating an assertion that drew a strong rebuke from the police union. Freeman told reporters that the officers' silence factored into his decision to call a grand jury.

"I've never had police officers who weren't suspects refuse to do their duty and come talk to us," Freeman said. "These are hard jobs and tough questions. The police patrol, investigate and present us cases — we evaluate those cases and have to make the charging decision and do the prosecution."

"There's going to be tension between those two roles but … we will not stop getting all the evidence, even if we have to ruffle some feathers."

Freeman had previously pledged to end the decades-old practice of using a grand jury in officer-involved shootings, a secretive process that he said lacked transparency and undermined public trust.

Bob Kroll, president of the Minneapolis Police Federation, the union that represents the department's officers, said in a statement that officers were simply advised of their rights, and none was told not to speak with investigators. He said many of the officers called to testify had nothing to do with the case. "No opinions were offered on what action to take with any of our members," Kroll said. "For Mr. Freeman to say this, he is either lying or perpetuating a lie told to him. This is evidenced by the fact that nothing in the criminal complaint was discovered during grand jury testimony."

Justin Terrell, executive director of the Council for Minnesotans of African Heritage, said he was having a hard time reconciling the day's events, given the criminal justice system's past mistreatment of minorities. Noor is Somali-American, while Damond was white.

"It is suspicious, to say the least, that the first time the system tries to get it right that it's a member of our community that is going to have to go through this," he said, adding that he didn't necessarily disagree with the charges. "There's a legacy of racism that black folks are to be feared and controlled, and a legacy of racism that white folks are to be protected."

'We both got spooked'

The charges are consistent with the initial information released by BCA investigators — that Noor's partner, Harrity, heard a loud sound coming from behind the vehicle moments before Noor fired his gun. Noor, who was hired in March 2015, has declined to speak with investigators, but Harrity's interview revealed more details about the night's events.

Harrity and Noor arrived in the alley behind Damond's home at S. 50th and Xerxes avenues. Their headlights were off and computer screen dimmed, but Harrity used the spotlight as they drove slowly down the alley. Harrity removed the safety hood of his holster over his gun before turning into the alley. Harrity, who joined the force in 2016, later recalled that he heard what he believed to be a dog before reaching the rear of Damond's home at 5024 Washburn Av., but did not get out of the car to investigate. He did not hear other noises.

As the squad reached the end of the alley at 51st Street, nearly 2 minutes after arriving, Noor entered "Code 4" into the squad computer, indicating that the scene was secure and no assistance was needed.

Harrity later said that just before the shooting, he and Noor were at the end of the alley waiting for a bicyclist to pass. Five to 10 seconds later, Harrity heard a voice, a thump somewhere behind him on the squad car, "and caught a glimpse of a person's head and shoulders outside his window."

"Officer Harrity said he was startled and said, 'Oh sh*t or Oh Jesus.' " Fearing for his life, Harrity said that he reached for his gun, unholstered it, and held it to his rib cage while pointing it downward.

He then heard what "sounded like a light bulb dropping on the floor and saw a flash." After first checking to see whether he had been shot, he looked to his right and saw Noor with his right arm extended toward Harrity but did not see a gun. Turning to look out of the window, he saw Damond, "who put her hands on a gunshot wound on the left side of her abdomen and said 'I'm dying' or 'I'm dead,' " the charges read.

Both men got out of the squad, Noor still clutching his weapon. Harrity told him to reholster his gun. Neither officer's camera was on at the time of the shooting, but both turned them on immediately afterward. Harrity began CPR, with Noor taking over before paramedics arrived at 11:49 p.m. Damond died at the scene.

The body camera captured a conversation between Harrity and his supervising sergeant, with Harrity saying, "She came up on the side out of nowhere," and "We both got spooked." He said Noor "pulled out and fired." At the time, he did not mention hearing a voice or a noise beforehand.

Ryan Masterson, a neighbor who lives directly across the alley from where Damond died, stopped Tuesday to place daisies at the memorial that he's helped maintain over the past eight months. He applauded Freeman's decision to charge Noor as the beginning of a long-awaited resolution to the case.

"The family will finally get some answers. There's a calming peace brought today," he said.

Star Tribune staff writers Liz Sawyer, Andy Mannix, Brandon Stahl, Randy Furst, and University of Minnesota student reporter Trevor Squire contributed to this report.

Tip brings new search for Blaine woman who went missing 30 years ago

Souhan: Fans turned Game 1 into something special. Now bring on Game 2