How did Kid Cann become Minneapolis' most infamous gangster?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Journalist Walter Liggett's crusade to expose the criminal underworld's grip on Minneapolis ended on a frigid night in a hail of bullets from a Tommy gun, as his wife and daughter watched helplessly just feet away.

The brutal 1935 murder bore the mark of a "gunman who is paid only for dead men and whose merciless professional tactics leave no trace," the Minneapolis Star reported. Liggett's widow told police she'd never forget the "snarling smile" of the man behind the gun.

"It was Kid Cann," she said.

The murder of Liggett would become one of the enduring mysteries surrounding Minneapolis' most infamous gangster, whose real name was Isadore Blumenfeld. The killing and Blumenfeld's trial garnered front-page headlines across America and beyond. It would also ripple through the highest levels of state politics.

A reader who contacted Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project, wanted to know more about this man whose name became synonymous with the city's underworld in the early 20th century.

The U.S. Justice Department designated Blumenfeld a "top hoodlum," a violent bootlegger who went on to lead an organized crime syndicate. Blumenfeld's defenders would describe him more like a folk hero — a Jewish immigrant who couldn't read or write, but forged a path to wealth and helped others like him.

Blumenfeld owned his reputation as bootlegger, but denied many of the allegations of his role in organized crime. He called himself a simple businessman. "Ninety percent of what was written about me is bull," he once said.

What is certain is that Blumenfeld helped shape Minneapolis by commanding influence over its political and business worlds. And in his rise to power, he achieved celebrity status.

"Kid Cann became perhaps the most famous Minneapolis figure other than Hubert Humphrey," said historian Paul Maccabee, author of "John Dillinger Slept Here" and other texts about mobsters in Minnesota. "Everyone knew Kid Cann. He was like the boogeyman."

Humble beginnings

Born in Romania, Blumenfeld emigrated to Minnesota with his parents in 1902 when he was 2 years old, arriving in north Minneapolis by way of Duluth.

His father — like many immigrants at the time — made his living as a peddler, Maccabee said. Blumenfeld spent his childhood on the streets picking pockets, delivering coffee for nickels and reselling bus transfers or newspapers he found in the trash.

Minneapolis was considered one of the most antisemitic cities in America at this time, severely limiting career choices for a poor, illiterate Jewish immigrant. But in 1920, the nation's constitutional amendment banning alcohol opened a new pathway for someone with his skillset and grit to prosper.

Blumenfeld rose from a petty thief in his early 20s to a millionaire during the 13 years of Prohibition. Through a bootlegging ring that stretched from Canada to New Orleans and Cuba, he helped flood the Twin Cities with rum and whiskey.

It is around this time that Blumenfeld developed his famous "Kid Cann" nickname, though its origins remain unsettled history. One theory is that it was derived from Blumenfeld's days as a young boxer, though Maccabee said there is no record he ever boxed. A less glamorous story is that Blumenfeld habitually hid in the bathroom — the "can" — whenever the shooting started.

Blumenfeld "hated, hated, hated" his nickname, Maccabee said.

"That's just a name the politicians or the newspapers use when they want to blame someone for something," Blumenfeld once told a reporter. "All you hear in this town is 'Kid Cann this' and 'Kid Cann that.'"

Later in life, Blumenfeld would ask people to call him Dr. Ferguson — or "Fergie" — perhaps a sign that he yearned for acceptance in the legitimate world.

Blumenfeld was arrested several times for bootlegging, but almost always avoided jail time. He was indicted in New Orleans, but the courts dropped the charges after he didn't show up for trial.

In 1924, Blumenfeld was named a suspect in a shooting on Nicollet Avenue, but a Hennepin County grand jury ruled it an accident. In 1928, he was charged in the shooting of two police patrolmen. Hennepin County Attorney Floyd B. Olson dismissed the charges, citing lack of evidence.

The death of Walter Liggett

By the time Prohibition ended, Blumenfeld had accumulated enough wealth and notoriety to be a power player in Minneapolis. His clothing and charming demeanor gave him an air of legitimacy as a political fixer in a time of government corruption. He operated out of the Flame Café on Nicollet Avenue.

If you wanted to open a nightclub in Minneapolis, Blumenfeld held sway over the liquor licenses. A well-placed bribe at City Hall could make a nosy health inspector lay off. In the early 20th century in Minneapolis, this was business as usual.

Killing a prominent journalist was not.

In the months leading up to his 1935 murder, Walter Liggett reported on Blumenfeld in Midwest American, the weekly newspaper he published with his wife. Liggett also fixed his crusade on one of the most powerful men in the state: Olson, who had been elected governor in 1931.

Liggett routinely printed an article of 10 reasons Olson should be impeached and mailed copies to state legislators. The list included "the sale of public office" to candidates who were "morally unfit." Edith would recall later hearing a phone call in which an associate of Blumenfeld threatened to sue Liggett.

"Go ahead if you think I can't prove what I say," Liggett said.

"I'll stop you some other way then," the caller replied.

In October 1935, Liggett was badly beaten. Police called it a drunken brawl instigated by Liggett. Edith reported in Midwest American that a group of men led by Blumenfeld had attempted to bribe Liggett and jumped him when he refused. Soon after, Liggett stood trial on sexual assault allegations, which his defense called a "frame up." A jury found him not guilty on all counts.

A month later, he was dead.

Liggett's daughter, Marda Liggett Woodbury, recalled riding in the back of her father's car after a trip to the grocery store on the night of Dec. 9, according to her book, "Stopping the Presses." They pulled into the alley behind their apartment, at 1825 2nd Av. S., and an "ominous" car followed close behind. Marda, who was 10, remembered her father motioning for her and Edith to stay in the vehicle.

A gun appeared from the other car's window and fired. Edith leapt frantically into the alley, where Walter lay dying from five bullets that "formed a tight crescent around his heart," Woodbury wrote.

Newspapers across America ran stories on Blumenfeld's alleged role in a critic's murder. That Olson had become the focus of Liggett's articles was enough to evoke him in the harsh critiques of the state of affairs in Minnesota.

U.S. Sen. Thomas D. Schall, R-Minn., characterized Liggett and two other Twin Cities journalists killed around this time as "the first martyrs of the cause of American freedom of the press since the Civil War."

Chicago Tribune publisher Robert R. McCormick called Liggett's killing "an effort to throw the entire press of the state under a reign of terror," attributing the murder to a "terrible alliance between crime and politics."

In his death, Liggett had accomplished his goal of casting a spotlight on corruption. But it did not last.

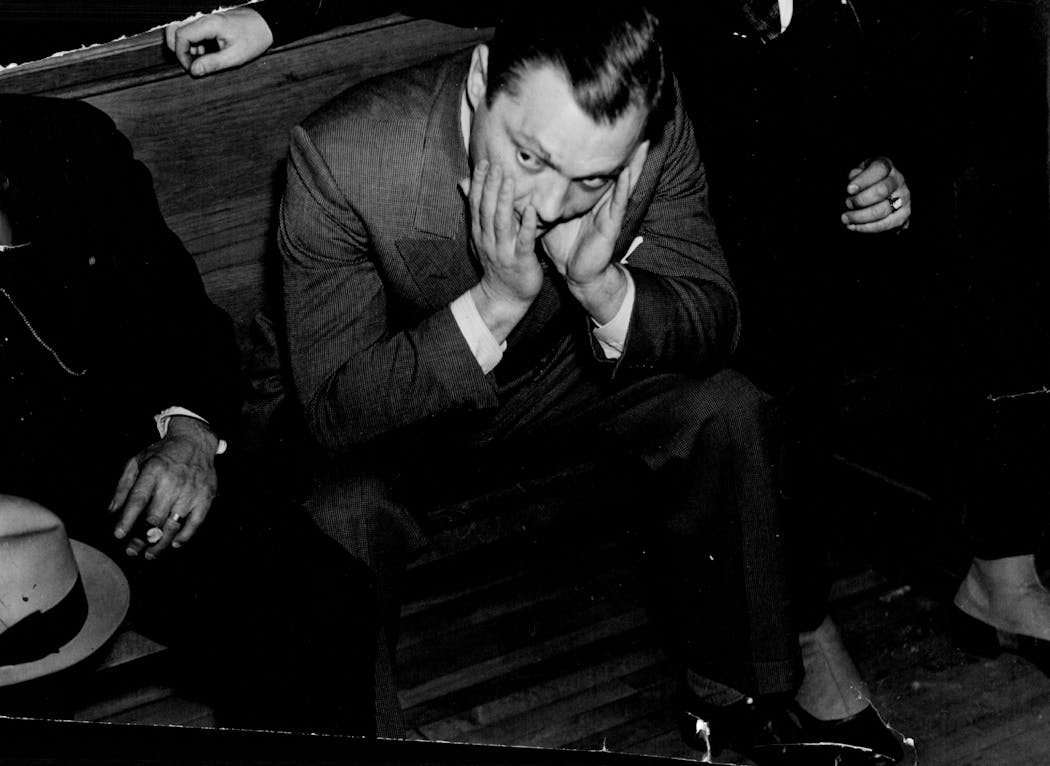

A grand jury indicted Blumenfeld in the killing. He claimed to have been in a barber shop at the time. A jury found him not guilty on all charges. Dressed in a dapper three-piece suit, Blumenfeld kissed the hands of female jurors who had acquitted him.

Streetcar racketeering scandal

Whether or not Blumenfeld killed the journalist would be litigated in the court of public opinion long after the jury delivered its verdict. Edith told reporters the acquittal was a forgone conclusion, and Blumenfeld's ties to power were too great for a court to convict him.

Maccabee said it's likely Blumenfeld ordered the murder, but he doesn't buy that he fired the shots. Blumenfeld wasn't a trigger man, he said, and there were plenty of others in town who were.

Not even a high-profile murder trial would keep Kid Cann out of business, however.

In the early 1950s, Blumenfeld participated in a scheme to buy a controlling stake in Twin City Rapid Transit Company, which ran the city's streetcar system. He claimed he quickly sold the stock. Soon, the streetcar system was being dismantled to make way for buses and the company had a lot of assets to unload.

In 1959, the federal government charged Blumenfeld and the others with a conspiracy to defraud the company of about $1 million by selling the materials at heavily discounted rates in exchange for kickbacks. Prosecutors claimed Blumenfeld was "one of the powers behind the scheme."

Several of the men involved went to prison. But Blumenfeld once again escaped unscathed.

'You have led a bad life'

Like Al Capone, Blumenfeld's undoing came from the least of his crimes.

Looking for a pathway to deport him, the federal government began conducting extensive investigations into Blumenfeld's sex life, said Maccabee, who obtained the gangster's Immigration and Naturalization Service file through the Freedom of Information Act.

Blumenfeld had developed a fondness for a 27-year-old prostitute, whom he paid to travel to Minneapolis from Chicago on several occasions. In 1959, prosecutors charged Blumenfeld and an associate with violating the White-Slave Traffic Act for moving her across state lines. A jury found him guilty in February 1960.

"You have led a bad life, Isadore," the judge proclaimed upon rendering his sentence.

Blumenfeld said he was "terribly sorry" and denied being part of any organized crime syndicate. "I haven't been no real bad man at all for 25 years," he said.

Blumenfeld served 3½ years in federal prison. After his release, he moved to Florida. Before he left Minneapolis, he told reporters his crime days were long over. "I don't need any more deals to make more money," he said. "I'd just like to be left alone."

In 1967, an investigative report in the Miami Herald named Blumenfeld "the biggest landowner" in the "flashy gold coast" of Miami Beach. The article tallied millions of dollars Blumenfeld and his partners were investing in oceanfront real estate. Blumenfeld had joined forces with legendary gangster Meyer Lansky.

Blumenfeld died of heart disease in 1981. Maccabee recalled being a reporter at the Twin Cities Reader, the now-defunct alt-weekly, when a colleague rushed into the office to announce the news: "The Godfather has died."

In Blumenfeld's final years, Maccabee said, Minneapolis residents who remembered the time of Kid Cann would swear they saw him in downtown brokerage offices. By then, the city had transformed. Large-scale corruption had lost its grip on politics. A new era of street crime was dawning, and the old breed of gangsters was already a distant memory.

Blumenfeld was just another old man checking up on his stocks.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Was organized crime behind the demise of the Twin Cities streetcar system?

Did St. Paul really protect gangsters during the Prohibition era?

Why does Minnesota have municipal liquor stores?

Where did streetcars once travel in the Twin Cities suburbs?

Was Minnesota home to nuclear missiles during the Cold War?

How did Dinkytown in Minneapolis get its name?