When I was growing up, my father owned a few shares of stocks in companies he liked, including 3M, General Mills and RCA.

General Mills once a year sent cereal samples to shareholders like him, and he gave them to me and my sister. What mattered more to him was that all the companies in his small portfolio paid dividends. That's what investing was about for decades, even centuries: the cash relationship between companies and their owners.

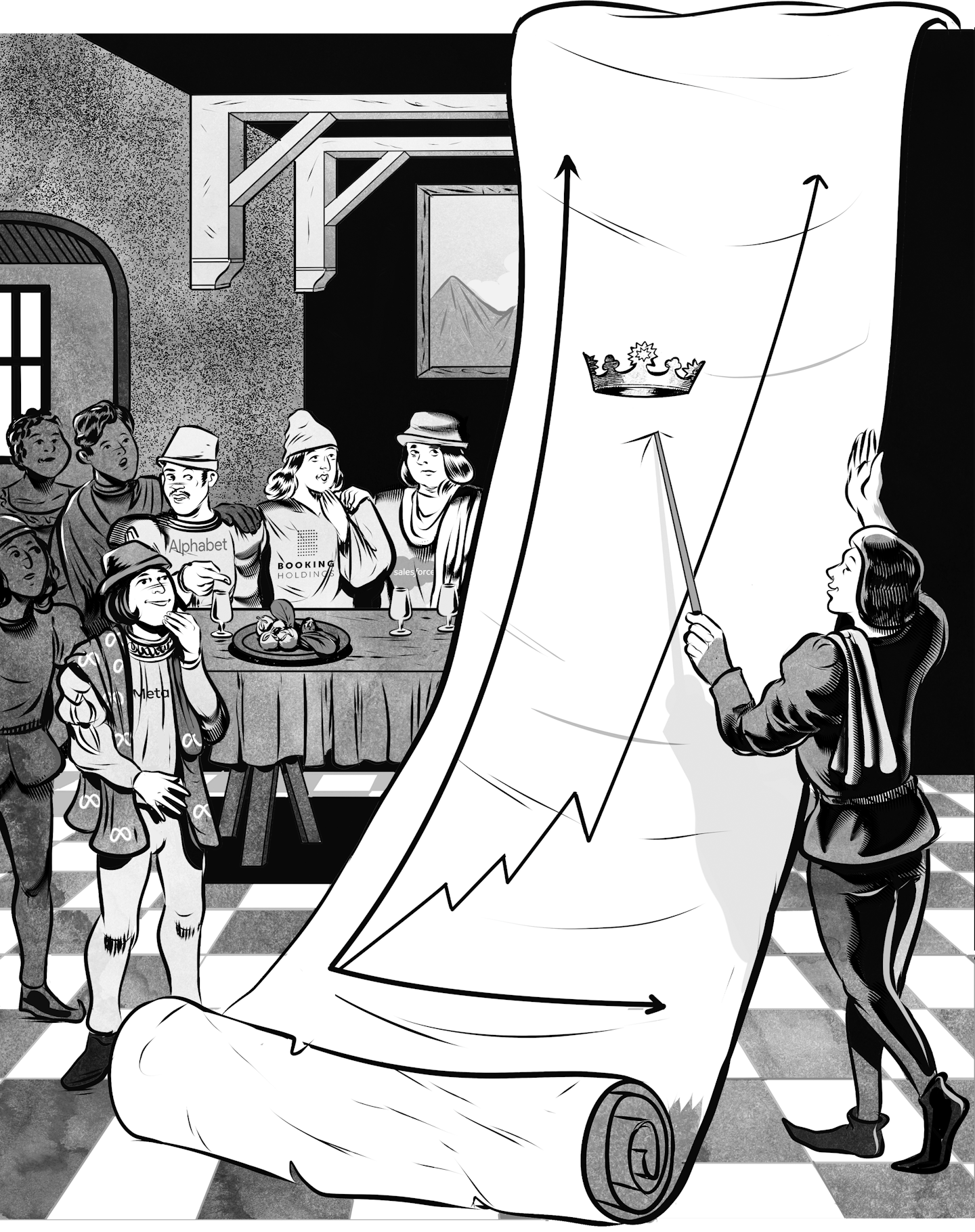

Over the last four decades, a period shaped by the relatively steady downward march of interest rates, investors chased big gains in share prices. Executives goosed those prices with share buybacks. Dividend investing became a niche strategy.

Now, the pendulum is swinging back. In the fight against inflation, interest rates in 2022 popped back up to levels unseen since 2000. Few people believe the ultralow interest rate environment of the 2010s and pandemic period will return.

In addition, the high-growth tech companies of the 2000s and 2010s are maturing. Nations are retreating from the neoliberal trade paradigm that fueled so much growth over the last 30 years. Stock buybacks are falling out of vogue. And investors are less tolerant of delayed returns.

Companies paying dividends, and funds built around those stocks, now have an advantage attracting investors.

As a result, people who manage retirement savings through 401(k)s and similar accounts will likely see more dividend-related funds as investment options in the future. Big fund managers such as Fidelity and Vanguard recently lowered fees on dividend funds, making them more competitive with index-based funds.

The Federal Reserve started raising rates in March 2022, but it took months for market commentators to grasp the epochal change at hand. One seen as having recognized it fairly early, Oaktree Capital Management co-founder Howard Marks, wrote his now-famous "Sea Change" memo in December that year.

"If you grant that the environment is and may continue to be very different from what it was over the last 13 years — and most of the last 40 years — it should follow that the investment strategies that worked best over those periods may not be the ones that outperform in the years ahead," Marks wrote.

Daniel Peris, a portfolio manager at Pittsburgh-based Federated Hermes and author of several books on dividend investing, calls this change the "return of the cash nexus." In an interview, he said, "It is investor insistence on a cash return, not just a price return."

There's no bigger sign of this change than the fact that several of the country's best-performing tech companies recently initiated dividends, including Alphabet, Meta, Salesforce and Booking Holdings.

Peris' latest book, "The Ownership Dividend: The Coming Paradigm Shift in the U.S. Stock Market," came out just days before Meta's February announcement of dividend payouts. He said he wrote the book in part to explain why earlier books that forecast the return of dividend investing, including some of his own, were wrong.

The first beneficiaries of the change, he said, will be people who have always preferred a cash-based relationship with their assets, including "the long-suffering widows-and-orphans traditional investor."

"The opportunity will increase for what had become boutique investors, that is dividend investors, in the stock market," Peris said. "I only see marginally good things in terms of discipline and capital allocation."

One argument corporate executives and their consultants make against paying dividends is that they indicate executives have nothing better to do with the company's cash. Share buybacks send that same signal, however. Meanwhile, dividends also send a more positive message of confidence in future cash flows.

David Bahnsen, a California-based investment manager, has long advocated investing in dividend-paying companies because dividends are a sign of strong management and real profits.

"We can select companies with the ability and propensity to grow the dividend; we cannot select or identify an 'ability to grow the multiple,'" Bahnsen wrote in a recent essay in John Mauldin's "Thoughts from the Frontline" newsletter.

That's a point Warren Buffett drove home in his letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway in April. He wrote that once more in 2023 Berkshire didn't make any move in two of its biggest, long-standing investments, Coca-Cola and American Express.

"Both companies again rewarded our inaction last year by increasing their earnings and dividends," Buffett wrote.

"Both Amex and Coke will almost certainly increase their dividends in 2024 — about 16% in the case of Amex — and we will most certainly leave our holdings untouched throughout the year," he added. "The lesson from Coke and Amex? When you find a truly wonderful business, stick with it. Patience pays, and one wonderful business can offset the many mediocre decisions that are inevitable."

Exceptions prove rules. Berkshire Hathaway remains one of the few giant American companies that does not pay a dividend. One reason may be the potential effect on Buffett and others who have owned Berkshire shares for decades.

Barron's reported earlier this year that if Berkshire Hathaway paid a 1% dividend, that would create annual income for Buffett exceeding $1 billion.